100 Million More Ticking Time Bombs

by Kevin Fitzgerald with David Schumann on April 27, 2021

Takata committed their first of many lies in the spring of 2000 when their PSDI driver inflator was exploding after exposure to Honda’s validation environments. The inflator was the first to showcase Takata’s new ammonium nitrate (PSAN) propellant called 2004, which promised a legion of smaller and lighter weight devices. Not having the courage to admit failure, Takata omitted the disastrous results from the validation report, and replaced them with false, passing data. They deceived Honda and pushed the PSDI into production while their chemists frantically searched for a solution. And in the fall of 2000, a propellant process change was made that allowed the inflator to squeak by Honda’s requirements without exploding. Takata revealed none of this to Honda and made no attempt to retrieve any of the defective inflators produced before the change. Thinking they had the problem solved, they rolled the dice on the small population and never looked back. But Honda’s specification was not difficult and in hindsight no predictor of how the inflator would age in vehicles.

As time marched on and millions of Takata PSAN inflators were sold to automakers around the globe, inflator specifications only grew more demanding. The process change made in 2000 could no longer mask the propellant’s sensitivity to moisture and as Takata moved to launch their second generation of PSAN inflators, post environmental ruptures were rampant. It was a cry for pause but having already strayed down the slippery slope five years earlier, the consequences of that were untenable. Takata had bet everything on PSAN, and their customers were eager for the compact airbags it delivered. So, the lies grew and the second generation, just like the first, was launched under false pretense, leaving Takata’s chemists still scrambling for a solution.

This time it wasn’t a process change that came to the rescue. A drying agent, or desiccant, was added to the inflator that enabled qualification to even the most extreme specifications. It was the silver bullet Takata was looking for and in late 2008, the X-Series was launched with a slightly modified PSAN to reduce cost called 2004L and desiccant. It was eight years from the first lie that unleashed tens of millions of Takata’s ticking time bombs into the world.

A desiccant is a material that readily takes up moisture and retains it. When placed inside an inflator, it protects the propellant from any moisture trapped during assembly or that makes its way in over time through leak paths. But a desiccant can only absorb so much before it saturates. When that happens, any further moisture heads straight for the propellant, and the clock on the time bomb starts ticking. Desiccant may extend the life of a Takata inflator, but not its ultimate fate – that is just a matter of time.

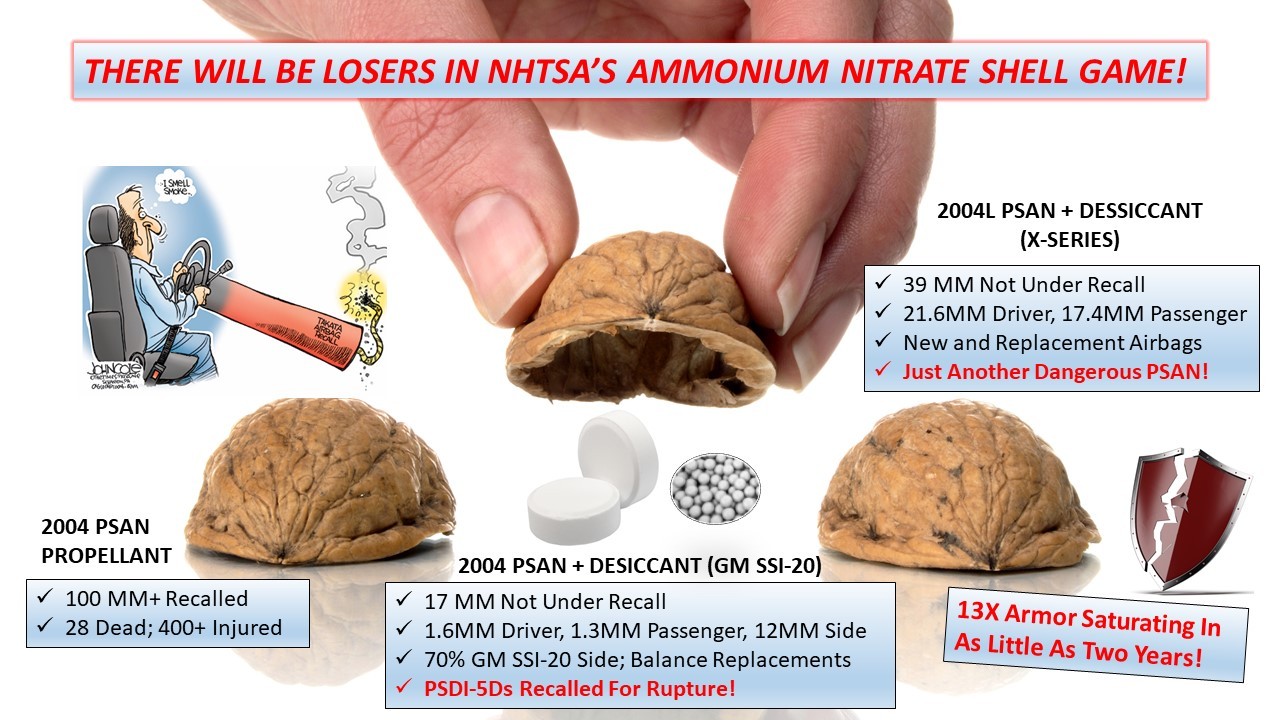

Takata produced over 200 million PSAN inflators – 100 million non-desiccated and 100 million desiccated. The non-desiccated inflators have taken 29 lives, injured over 400 and are under recall. The 100 million desiccated inflators are not under recall. 56 million of those are in the U.S., and automakers are desperately clinging to the belief that they are safe. By the end of 2019, the National Highway Traffic Safety Association (NHTSA) was to decide on their outcome, but didn’t. Instead, they waited until May 2020, at the height of the global pandemic, to announce they were siding with a coalition of automakers to leave the inflators on our roads and in our faces. What follows is our take on this life-threatening decision.

Our Rebuttal

When announcing their ruling, NHTSA’s stated that “none of Takata’s desiccated inflators pose an imminent risk to safety,” basing their claim on two reports submitted to the agency six months prior. One was one from a group of automakers known as the Independent Testing Coalition (ITC), and the other was from Takata. A third and more damning report was released a month after the ruling by an engineering consulting firm called Exponent. NHTSA claims to have also considered this report. We find that to be impossible.

The Reports

The ITC and Takata reports are literally devoid of any worthwhile data. The coalition’s conclusions center on an unvalidated Northrop Grumman computer model lacking any long-term, desiccated inflator field data. In fact, in their report, the ITC pleads with NHTSA to begin an X-Series field monitoring program because without that data their computer models are of little to no value. Takata’s report is even less substantial, and really, why haven’t they just taken a seat and zipped it already? Exponent’s report, however, the one NHTSA doesn’t like to advertise, is supported by a field return aging study, and their computer models paint a much darker picture than Northrop’s.

The Independent Testing Coalition (ITC)

Let’s pause here to explain who the ITC are. They deserve a little scrutiny since NHTSA is placing all their trust in them. The coalition consists of ten automakers all with a vested interest in avoiding any further recalls. There are still 20 million non-desiccated Takata airbags on our roads six years into the first campaign due to this group’s indifference. Why on earth would they want to add another 56 million? They don’t, and to make sure of it, they locked arms with the mighty Northrop Grumman to scare off any would be challengers to their technical competence. It’s disturbing to see what has happened to NHTSA’s decision making process.

Manufacturing Miscues

Pleading for a field monitoring program isn’t the only reoccurring theme in the ITC report. They also made it profusely clear that their predictions did not consider Takata’s long and well documented history of manufacturing errors. Takata brazenly made the same disclaimer in their report, which is just plain offensive. So, let’s see how this plays out in real life. The coalition’s computer models predict the desiccated PSDI-5D driver inflator, that Takata began producing in 2014 as a replacement part, will last 25 years no matter the vehicle size or climatic location. But just five years into production, in 2019, one exploded and lodged a fragment in the driver’s arm that initiated a recall of the entire population. And the root cause? Manufacturing errors involving moisture. Clearly, Takata’s miscues cannot be excluded from the equation.

This passage from a May 2020, Consumer Reports Article titled, Safety Experts Fault Regulators for Limiting New Takata Airbag Recalls to Volkswagens also questions NHTSA’s judgement for not considering Takata’s spotted manufacturing record.

On their face, the reports address the varying risks of different airbag designs. But they fail to address some important details”, says Shawn Kildare, Ph.D., Director of Research at Advocates for Highway and Auto Safety, an alliance of consumer, health, and safety groups and insurance companies that promote automotive safety.

For example, the reports did not disclose whether there were any manufacturing errors that could also shorten the lives of the airbags—an important point, since some of the prior Takata airbag recalls have been the result of past production errors. The reports also failed to disclose the potential risk of injury to drivers—and only included the risk that the airbags would fail.

Those are all the nasty details that could really have an impact on people’s lives,” Kildare told CR.

Takata made countless manufacturing errors that could shorten the lives of the inflators, far more than they ever divulged. That is an indisputable fact, revealed by one frightening episode after another in our book. Just look at the pen I wore down doing my best to prevent defects from escaping. Arrows slipped through. NHTSA knows it. It’s just one of those nasty details.

Garbage In = Garbage Out

Northrop Grumman’s computer model is the linchpin of NHTSA’s ruling. It defines when an airbag’s inflator has a 1 in 10,000 chance of exploding based on inflator type, vehicle size and climatic region. It’s also a perfect example of a concept common to mathematicians and computer scientists alike – the quality of a model’s output is governed by the quality of its input, and in the case of the Northrop Grumman model, it spit out exactly what it was fed – Garbage!

The simulation uses critical density, the point at which a propellant becomes problematic, to predict timelines to failure and the value input by Northrop Grumman is twice the drop from initial density that any Takata engineer would ever tolerate. Setting the value this low causes the model to grossly overpredict the time it will take to reach that 1 in 10,000 catastrophic event. Case in point – The simulation says the PSPI-L used in the 2010 Chevy Silverado will last 21 years in Miami’s searing heat and humidity. That’s another 10 years from now. But just one year after the model’s results were published, NHTSA ended four years of GM stalling and mandated the vehicles be repaired, nine years shy of the Northrop Grumman expiration date. The linchpin is clearly unreliable.

Exponent, on the other hand, conducted lab accelerated aging of PSPI-X passenger inflator field returns to correlate their model and when they went to measure internal pressure, inflators started exploding! Using real world data, Exponent predicts a ghastly 1 in 200 chance of a PSPI-X rupture after only 16 years in Miami. The ITC, with no long term X-Series field data, says that chance is only 1 in 10,000. Those predictions aren’t even close! With that great a discrepancy, how could NHTSA have decided at all and worse, how could they have sided with greater public risk?

Saturated Desiccant and the Propellant Shell Game

We saved this bombshell for last. You won’t find in either the ITC or Takata report that the desiccated inflators are saturating in as little as two years. No, that jaw-dropper can only be found in the Exponent report. Interestingly enough, Takata assisted in that study yet failed to communicate its devastating findings. With X-series inflators in vehicles as long as 13 years, Takata and the ITC knew many were already saturated. The desiccant was no longer enough to differentiate them, or any desiccated inflator, from the 100 million already under recall.

Switching gears, Takata claimed the PSAN adjustments introduced with the X-Series to reduce cost also had the added benefit of slowing down the aging process by increasing the propellant’s resistance to moisture penetration. Pair that with a desiccant and a second recall wasn’t necessary. Sleight of hand at its best, but here’s the truth folks – the X-Series’ PSAN (2004L) is just another dangerous, moisture sensitive ammonium nitrate, and the armor protecting is breaking down rapidly.

And if that wasn’t confusing enough, take a peek under the middle shell. That’s another bombshell NHTSA doesn’t want us to know about. Thirty percent of the desiccated inflators they are not pulling back, almost 17 million, have the original PSAN formulation (2004), the one already responsible for immeasurable pain and suffering. It is impossible to understand NHTSA’s logic. With the desiccant in these inflators saturating quickly, the only reasonable action is to relegate them to the first recall population. Seventy percent are GM’s SSI-20 side impact inflators whose desiccant only has capacity for built-in moisture and not ingress. It’s long past their time to come home.

Wrap Up

We wrote In Your Face because we knew NHTSA would side with the automakers and leave Takata’s 56 million desiccated inflators in our faces. The cost was just too astronomical for the lives that would be saved. The book was our preemptive strike to the ITC and Takata reports, this rebuttal serves as our return salvo.

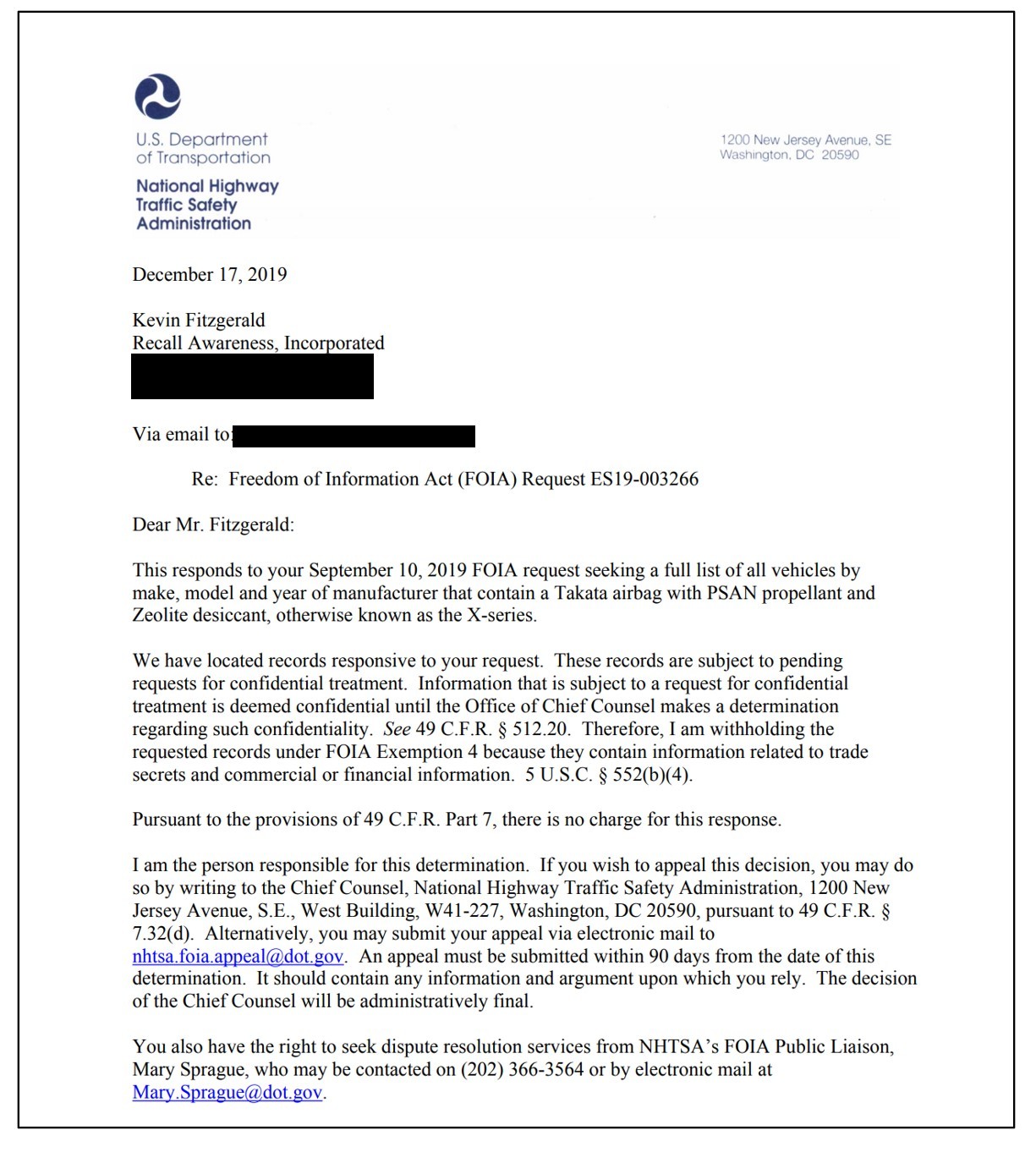

A year has passed since NHTSA’s disastrous ruling, and search engine results for X-Series field monitoring activities still come up empty. Those programs were the only thing that brought any sanity to NHTSA’s decision. If the driving public can’t access their results or worse, the studies aren’t even happening, then the list of vehicles these airbags are in must be made public. We can’t fight back if we don’t know we are impacted. A year earlier, I submitted a Freedom of Information Act request for this record. Here is what I received in return.

NHTSA must change. They have devolved into a captured regulatory agency, controlled by big money and the lure of fat industry jobs. We believe 50, 75, 100 lives saved, and thousands of injuries prevented is worth the billions in automaker profit this will take to clean up. NHTSA disagrees, so it is left to us. We must take charge and demand that all Takata airbags, desiccated or not, come off our roads or we will be forced to suffer the consequences for decades to come.

Elba Pabon

February 4, 2020 at 11:05 pm

The 2017 Nissan Altima had a recall in 4/29/2016 and it wasn’t public and the vehicles were never taken care of according to NHTSA, one of those airbags almost left me blind on my right eye